BREL - Songs of Life, Love and Death. 2010 REVIEWS

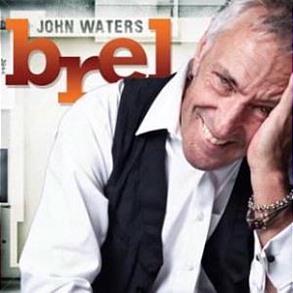

JOHN WATERS PERFORMS THE SONGS OF THE LEGENDARY JACQUES BREL IN FRENCH

One of Australia’s most recognised and respected actors and singers, John Waters will perform a concert that highlights the songs of the great French Chanson singer-songwriter Jacques Brel.

While many of Brel’s songs were recorded in English translation in the 60’s and 70’s by artists including Frank Sinatra, Neil Diamond, Dusty Springfield and Ray Charles, Waters will perform them as their original French versions, explaining their significance along the way – sometimes comic, sometimes tragic, sometimes painfully romantic but always engrossing and compelling.

Waters has been inspired by Brel’s songbook since he was in his teens, leading him to perform these incredible songs in late night shows in Sydney’s Kings Cross in the early 1970’s. This eventually evolved into the critically acclaimed tribute show Café Brel in 1999.

Now in this brand new incarnation, simply titled BREL, Waters will create and assume the character again, telling stores rich in dimensions that will arouse and entice you into the world and music of Jacques Brel.

To coincide with the tour John will make available at the shows only his “LIVE AT THE SEYMOUR” recording of the BREL show. Containing 15 tracks, the album superbly captures the raw emotion and expert delivery of BREL.

“As a teenager hitchhiking in France I meet a street musician singing a beautiful song. I asked who’s song it was and he said Jacques Brel and that memory and the passion expressed in the song is something I’ve wanted to revisit ever since. I also had the fortunate pleasure of seeing BREL live in performance at the Olympia in Paris and I perform his works as often as I can” says John.

If you saw Water’s popular John Lennon tribute ‘Looking Through A Glass Onion’ and loved it, then BREL is sure to cast a spell and get under your skin.

“Waters makes the French connection.” Sydney Morning Herald.

Passion and sex, life and death - why Jacques Brel rocks. By BERNARD ZUEL. June 8, 2010. Sydney Morning Herald

Channelling . . . Waters gives songs "the same flavour" as Brel did.

IN RETROSPECT it may seem obvious that John Waters would be seduced by the songs of Jacques Brel, which he sings in a show devoted to the spirit as much as the music of the man regarded as one of the great songwriters of the 20th century.

The young Waters, living in south London in the early 1960s, would hop on a ferry across the Channel to discover the more romantic, more exotic and erotic offerings on the Continent. At home, Cliff Richard or Perry Como sang of sweetness and light or the delights of a cardigan, and the Beatles and Smokey Robinson trilled of love.

But Brel, the Belgian-born giant of the French dramatic song form known as chanson, sang of soldiers, whores and drunkards, of grand passions cast on the rocks like crumpled ships. Now that's living, as singers as disparate as Scott Walker, David Bowie, Rod McKuen, the Kingston Trio and Judy Collins knew all too well in their later English versions of Brel songs.

In the port of Amsterdam, in the words of Brel, ''there's a sailor who dies/Full of beer, full of cries/In a drunken town fight'' - but, as Waters ruefully confesses, he most often travelled to the far less romantic port of Ostend in Belgium (''not exactly the most exciting town in the world'', he sighs). Luckily, a side trip to the south of France and an encounter with a busker singing Brel's Le Plat Pays, followed by a chance to hear Brel in a farewell concert in London, turned the then 17-year-old's head.

''It surprised me that I liked it but when I thought about it, it's not so strange for someone who is into rock'n'roll music as I was,'' Waters says. ''I believe that the kind of immediate passion and the basic themes of sex and life and death are very similar to rock'n'roll, although this is a uniquely European, Gallic form of song, really.''

Even as he explored the rock and soul of the late '60s, moved into acting and music theatre and migrated to Australia to appear in Hair on stage and later Rush on the ABC, Waters kept hold of Brel. He was probably the only cast member in the early '70s Sydney production of the English-language review Jacques Brel Is Alive And Well And Living In Paris who knew the songs. Definitely the only one who knew them in French.

Two decades later when the success of Glass Onion, his stage show based on John Lennon, became such a success he took it around the world, Waters came back to Brel. In its second incarnation, after a brief tour 12 years ago, Brel is intense, dramatic and unapologetically French.

''In singing the Brel songs, one of the reasons I sing them in French is because I don't think you can separate a song from its sound. And that means of course its language and the use of vowel and consonant and the percussive nature of the language that Brel uses,'' says Waters, whose French is fluent. ''When I sing the songs I don't consciously think, 'Now I'm going to do a spot-on impersonation of Jacques Brel', but I like to give them the same flavour that he gives them.''

There are few things that are inconsequential in a Brel song - he trafficked in strong emotions and extremes - and it doesn't matter if you know the language; you just understand.

''In some ways I like singing these songs to an English-speaking audience because they really listen to the passion and the musicality of the songs,'' Waters says. ''If they don't get the exact meaning of every word it's never been a problem.''

John Waters performs Brel at the Basement on Sunday and Lizotte's, Central Coast, on June 24.

John Waters. Brel, The Basement, June 13. REVIEWED BY JOHN SHAND Sydney Morning Herald. June 15, 2010

WHERE Cole Porter, another of the 20th century's greatest songwriters, had gently mocked or swooned at love, Jacques Brel gouged its eyes in despair, or bit its neck in reckless passion. Such vivid emotions punch their way from the songs even when exclusively sung in French, as John Waters did here in launching his album Brel.

Less than a month after the peerless Ute Lemper delivered the coup de grace to several Brel songs, it was fascinating to hear how well they responded to Waters's radically different treatment. They often dance along that fine line between melodrama and knife-in-the-heart emotional reality, and only once did the gritty, rasping Waters stray to the wrong side.

That was Ne Me Quitte Pas, perhaps Brel's masterpiece, when Waters overplayed a lyric that must be underplayed to truly catch the protagonist's desperation in the face of losing his love.

He was much more convincing conveying the delirium of Brel's vision, which is populated by dreamers: not guileless rhapsodists, but miscreants with distorted expectations of an even more twisted world. He nailed a rousing Mathilde and the macabre Le Tango Funebre (about the thoughts of the corpse of a family patriarch as he awaits burial).

Stewart D'Arrietta's arrangements for an expert sextet were mostly clever and detailed without being distracting, with J'Arrive being especially striking. La Chanson des Vieux Amants was too lush, however, compounding Waters's difficulty in milking the song's essence.

Le Dernier Repas contains some of Brel's finest poetry, which Waters growled and spat into acute life, amid glorious intersecting lines doubled by Craig Walters's soprano saxophone and Michael Kluger's accordion. The latter was also crucial to the success of La Valse a Mille Temps, as charm evolved into giddy madness.

Waters delivered Le Gaz with delicious self-deprecating comedy, then ripped into Amsterdam, lacing each word with venom, although the accompaniment peaked too soon. Marieke carried yearning and potent conviction.

Cabaret Festival: Brel, John Waters. The Independent Weekly. By NICKY TITCHENER. 17 Jun, 2010

John Waters has had many incarnations, from his early R&B bands in the 1960s to the much-loved presenter of Play School and, recently, the anarchic Dr Vlasek in All Saints.

This opportunity to see him channelling the spirit of Belgian composer and Francophile Jacques Brel gave the audience at the Dunstan Playhouse a completely different perspective on the charismatic actor.

Brel was a composer and performer of songs which Edith Piaf described as “expressing his reason for living”. Waters captured much of the grit and despair of life experienced through lost love, passion, dreams and even death – the Gitanes-laden huskiness of his voice was perfect for these – but he was also able to give lightness and humour to Brel’s more comic compositions, such as “Le Gaz” (a tradesman’s thoughts as he enters the house of a beautiful lady to fix a gas leak) and “Le Tango Funebre” (in which a corpse speculates about the motives of those who have come to bid him farewell).

John Waters puts across the songs with a sharp French delivery, but precedes each one with a resume in English of what you are about to hear so non-French speakers can still enjoy the performance.

Supported by six superb musicians who set a brisk pace throughout the show and created a wonderful ambience, Waters engaged the audience from the outset to the final encore – a salute to love, punched out with passion and energy. The packed audience responded with equal enthusiasm. – At the Dunstan Playhouse until June 19.

lifemusicmedia.com; John Waters – Brel @ Playhouse Theatre, 25th June 2010 posted on Jun.27, 2010, Review: Lana Harris

The piano player starts up, an accordion bursts in, and by osmosis of memory into reality, the room is filled with a cloud of collective audience thoughts of France. Personal artistic journeys for one, a package holiday with Eiffel tower earrings for another, access to the iconic baguettes and berets for those who haven’t been. This is the invocative power of Jacques Brel, a Belgian musician and artist who created his songs in the language of love. Never heard of him? He is mostly known in the English speaking world through his songs which have been translated and interpreted, but performers of these works include Frank Sinatra and The Dresden Dolls among many others. John Waters’ memories of Brel and his works start from a hitchhiking experience in France where Waters overheard a street musician playing a song whose passion captivated him. The song was Brel’s.

Since that time Waters has embellished the original experience by seeing Brel perform live, and Waters now tours his own shows of Brel’s works. He performs them “as often as I can” and they are brought to Brisbane tonight as part of QPAC’s week long cabaret festival.

A broad selection of musicians have been gathered to help Waters convey the magic of Brel. The singer performs with an accordionist, pianist, percussionist, saxophonist and two guitarists, some of whom jump to other instruments as the songs necessitate. Waters moves like a marionette to their sounds, arms extended, hands waving, rake thin grey suit legs twisting and flicking at the mercy of his tapping, rolling, springing feet, French phrases spilling indiscriminately from his lips. He performs the first song with no introduction, using humorous gestures to convey that the song, in part at least, is about wine and women. Fortunately for those of us who do not speak French, the rest of the songs are introduced by Waters’ summary and interpretation of their lyrics. Waters, who has a background in acting as well as song (most recently, he was part of the TV movie UnderBelly: The Golden Mile) delivers these synopses alternatively in humorous, dramatic and irreverent ways, and the stories become as much a part of the show as the music is.

The first tale we hear is about a man, losing his virginity. In the army. In the Mobile Military Brothel. Waiting in line for the occasion, he listens as his commander yells out ‘Next!’ at irregular intervals until, shuffling forward naked except for a towel, his first foray into the carnal world is anointed with a case of venereal disease. “Looking back, the man sees his place in the world ‘Next!’, as one of the endless line of the following and the followed ‘Next!’, never to be number one.” It’s not easy to tell how much of the poetry is in the song, and how much comes from Waters’ skilled translation. The song and sounds that follow are more light and jaunty than seem fitting given the tale told beforehand. The next tale speaks of love, not new love but old love, the love between people who know all of each other’s tricks, how the games are played and how they end, and yet still retain play and passion “knowing its okay to grow old, but not to grow up”.

This tale is told with musical worship, all minor scales and melancholic yearning chords, complemented by the French verbs and accents falling from Waters’ lips.

Even death was covered in the wide ranging themes: one tale started with a dead man reflecting on his life as he lay awaiting his funeral, another focused on the concept of the last meal, a last life experience, a last drink and love and irreverent yell at God and the bourgeois – Waters finished this performance by giving the finger to the crowd. While the songs themes were not always clearly linked to the sounds which accompanied them, it was interesting to note the format of the songs did not swing from verse to chorus and back again, but ebbed and flowed without a strong pattern

except for a swelling of sounds and emotions at the appropriate places in the often emotional tales. This was most evident in a song which Waters described as “Renoir on acid” – imagine a painter on drugs transforming the colours into words and rhymes. The music was a maelstrom, starting with a funny waltz introduction before invoking rich brass sounds, becoming forceful and frantic and building to a raucous, drunken finish as Waters hurtled his voice into the crowd.

Waters performing Brel was mind expanding. Experiencing songs without the burden of lyrics but with a poetic description of the intent was a unique experience which allowed both the beauty of the tales and panache and verve of the music to be appreciated separately. This was enhanced within the jazz styled form of following the story with the music rather than constraining it with choruses. Waters combined the best of his acting and voice talents to present an intriguing, amusing and enjoyable evening of cabaret.

One of Australia's most respected actors and singers, John Waters releases this brilliantly performed "live" recording of the great French Chanson singer-songwriter Jacques BREL. Brel's songs have been covered by the likes of Frank Sinatra, Neil Diamond, Dusty Springfield, Ray Charles and many others, but John Waters is the first Australian to release a full French version of the classics. 15 tracks covering the spectrum of life, love and death and sung with such emotion and power that one isspellbound and in awe of the brilliance of the multi talented John Waters.

BUY THE CD HERE

AT HOME............WITH ACTOR JOHN WATERS. 23 July 2010. From blog somehometruths.blogspot.com

When you are an actor, a singer or an entertainer you tend to live a very itinerant lifestyle following work all over the world. John Waters knows this life well; not entirely due to his own 40 year long career (both as an actor and singer) but because he also grew up with a father who was an actor.

‘It’s not an ideal way of life for small children and I am keenly aware of that with my own children so we try to keep home as stable as possible even though I’m here one day and gone the next.’

The last couple of months have seen John touring around Australia performing the songs of the 1950s Belgian-born French singer Jacques Brel. His music is dramatic and passionate and much of it explores his ideas about home, house, place and country. It is these themes that resonate deeply for John and have done since he first heard Brel’s songs as a 17-year-old travelling around France.

‘I still feel very strongly about the building I grew up in, a two-bedroom flat in suburban Teddington, south-west London. It was an unspectacular flat in an unspectacular area: an old Georgian building that had each floor converted to flats in the late 1940s. My parents rented it and brought up five children there.’

The flat stayed within the Waters’ family for more than 50 years and when it was sold 15 years ago John found it quite a loss.

‘As a small child I used to feel very insecure about being away from this building and from the people within it, but as a teenager I did everything I could to be away from it. I now look back and think that my desire to get away from that home was actually a desire to overcome my strange fear of being away from it.’

After leaving home at the age of 17 to travel around Europe, John eventually made his way to Australia and never returned to live in that flat. Yet, whenever he goes back to London he will always return to that building.

‘I always go back to walk those streets and stand out the front of that building and stare at it. Teddington, the river and the park surrounding it will always be very dear to me. I love that I can stand in the streets I kicked a football around, see the two skinny trees in the clearing there by the church that framed the goalposts of the makeshift pitch when I was eight years old.’

Brel once said that it’s important to progress in life but that it’s also important to return to where you come from. People unable to do so, he thought, were dislocated and would always feel a sense of loss and dislocation. John feels a strong affinity with this idea and was fascinated with Brel’s love/hate relationship he had with his home country, Belgium.

‘Brel writes very emotionally about the place, even though he feels he escaped. The intellectual side of him told him Belgium was a backwater; considered the sticks for French people yet he also has a strange affection about it and the land itself and finds beauty in it.’

‘In one of his songs, Le Plat Pays, he describes Belgium as a flat land, harsh, bitter, featureless with no mountains except the steeples of the churches (and he was haunted by the spectre of organised religion). For three verses he continues to describe how hard it is to love such a country and then in the final verse it explodes musically into different chords and becomes more lush. “When the south wind blows, the beauty is returned and the whole land begins to sing.” It’s very moving.’

Expected to take over his father’s cardboard carton company, Brel was born into a middle-class family who didn’t understand his artistic ability. As John explains, ‘In another song, Mon Enfance, he describes his life as a little kid who was a dreamer and was ignored by these fat, Flemish men who smelt of cheese and tobacco. He sings that in summer time he would play cowboys and Indians even though he knew “ my fat, old uncles would steal the far west from me; they would take my dreams away”.’

John continues that Brel also wrote songs with a degree of affection for this mismatched family. ‘He writes about his family as a tribe who only seem to come to life when there is a death. Later in his life, he talked about the “great house which had thrown its anchor just to the north among the jonquils.” His imagery is really beautiful; this idea that the house looked like it had drifted away from the rest of the town.’

Such a strong sense of a childhood home perhaps comes from people who travel, John thinks. ‘You need to leave home – leave your country – to get that sense. My brothers and sisters who still live in London certainly feel strongly about our flat but I don’t think they feel it as keenly as I do.’

Perhaps Brel’s most affecting and poignant song is J’arrive about a young, dying man. ‘It’s a very autobiographical song although I’m not sure that when Brel wrote it he knew he was going to die at the age of 48 but he was always haunted by the idea of premature death’, says John.

‘In the song this young man is saying ‘I’m coming, I’m coming but why now? Why me? Before I go I want to see once more if the river is still a river; to see if the place I come from is still there; to see myself in that place once more. The place where I first entered the world; where I was born.’

For John, he will always belong to two countries, ‘My Englishness stays because I keep travelling back. Sometimes I will return to London just to read the paper, have conversations about politics and football and once I’m immersed in that world I feel ready to return to Australia.’

But also for John, thoughts of returning to Teddington ‘just one more time; to see if the place I come from is still there’, are not strong. ‘Now I have young children again, I see the future through them. What I love about having children at this age is that it has given me something about the future to look forward to. The future now, for me, keeps going through them.’